- Mysteries of the Universe -

When NASA began 60 years ago, we had questions about the universe humans had been asking since we first looked up into the night sky. In the six decades since, NASA, along with its international partners and thousands of researchers, have expanded our knowledge of the Universe by using a full fleet of telescopes and satellites. From the early probes of the 1950s and 1960s to the great telescopes of the 1990s and 21st century, NASA scientists have been exploring the evolution of the universe from the Big Bang to the present.

Pillars of Creation, Eagle Nebula, a cloud of gas and dust created by an exploding star from which new stars and planets are forming.

Image Credit: NASA/ ESA/The Hubble Heritage Team (STScl/AURA)

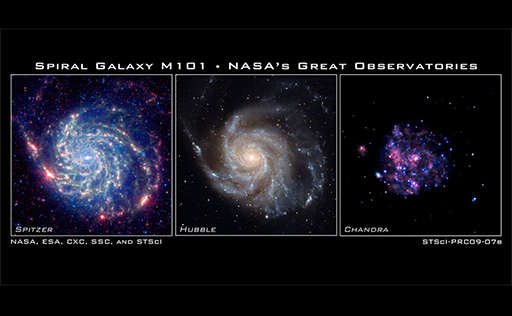

The Great Observatories

NASA astronomers use several kinds of telescopes in space and on the ground. Each observes targets like stars, planets, and galaxies, but captures different wavelengths of light using various techniques to add to our understanding of these cosmic phenomenon.

Image Credit: NASA

Hubble

Since it was launched in 1990, Hubble has forever changed our idea of what the universe looks like. It does not travel to stars, planets or galaxies, but takes pictures of them as it whirls around Earth at about 17,000 mph.

Image Credit: NASA

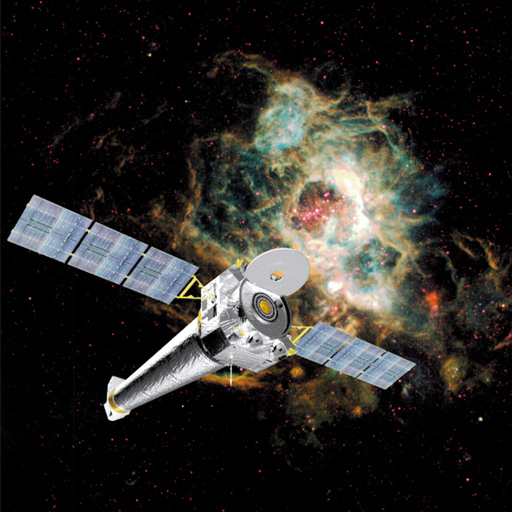

Chandra X-ray Observatory

The Chandra X-ray Observatory allows scientists from around the world to obtain X-ray images of exotic environments to help understand the structure and evolution of the universe. X-rays are produced when matter is heated to millions of degrees. X-ray telescopes can also trace the hot gas from an exploding star or detect X-rays from matter swirling as close as 90 kilometers from the event horizon of a stellar black hole.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Spitzer Space Telescope

NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, designed to detect primarily heat or infrared radiation, launched in 2003. Spitzer's highly sensitive instruments allow scientists to peer into cosmic regions that are hidden from optical telescopes, including dusty stellar nurseries, the centers of galaxies, and newly forming planetary systems. Spitzer's infrared eyes also allow astronomers to see cooler objects in space, like failed stars (brown dwarfs), exoplanets, giant molecular clouds, and organic molecules that may hold the secret to life on other planets.

Exciting Discoveries

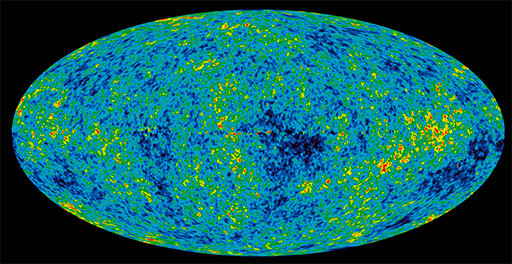

Image of the infant universe 13.7 billion years created from WMAP data, showing differences in temperatures that became “seeds” for galaxies.Image Credit: NASA

The Age of the Universe

The Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) satellite returned data that allowed astronomers to precisely assess the age of the universe to be 13.77 billion years old and to determine that atoms make up only 4.6 percent of the universe, with the remainder being dark matter and dark energy. Using telescopes like Hubble and Spitzer, scientists also now know how fast the universe is expanding.

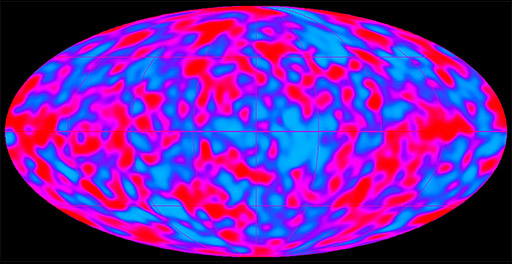

These minute temperature variations (depicted here as varying shades of blue and purple) are linked to slight density variations in the early universe. These variations are believed to have given rise to the structures that populate the universe today: clusters of galaxies, as well as vast, empty regions.Image Credit: NASA

How the Universe Began and Evolved

The Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE), launched in 1989, studied the radiation still left from the Big Bang to better understand how the universe formed. In 2006, John Mather of NASA and George Smoot of the University of California shared the Nobel Prize for Physics for confirming the Big Bang theory using COBE data.

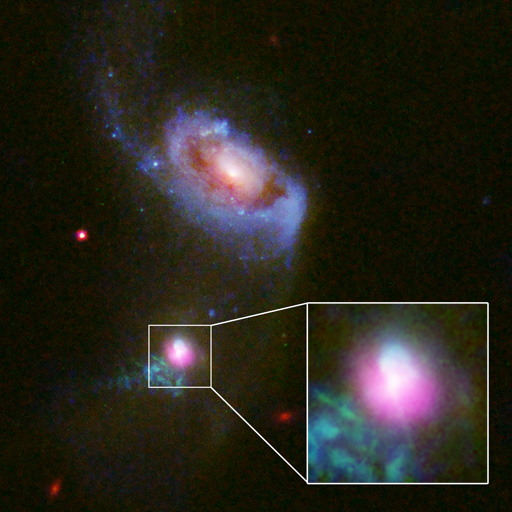

Dark Matter

NASA telescopes have helped us better understand this mysterious, invisible matter that is five times the mass of regular matter. The first direct detection of dark matter was made in 2007 through observations of the Bullet Cluster of galaxies by the Chandra x-ray telescope.

Image Credit: X-ray NASA/CXC/University of Colorado/J. Comerford et al.; Optical: NASA/STScI

Black Holes

Although we can’t “see” black holes, scientists have been able to study them by observing how they interact with the environment around them with telescopes like Swift, Chandra, and Hubble. In 2017, NASA's Swift telescope has mapped the death spiral of a star as it is consumed by a black hole. This year, astronomers using Chandra have discovered evidence for thousands of black holes located near the center of our Milky Way galaxy.

Image Credit: Image Credit: NASA/ESA/G. Dubner (IAFE, CONICET-University of Buenos Aires) et al.; A. Loll et al.; T. Temim et al.; F. Seward et al.; VLA/NRAO/AUI/NSF; Chandra/CXC; Spitzer/JPL-Caltech; XMM-Newton/ESA; and Hubble/STScI

Crab Nebula

Image of the Crab Nebula, combining data from several telescopes. The Crab Nebula, the result of a bright supernova explosion seen by Chinese and other astronomers in the year 1054, is 6,500 light-years from Earth.

Image Credit: NASA/ESA/A.V. Filippenko (University of California, Berkeley)/P. Challis (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics), et al.

A Bright Supernova

The explosion of a massive star blazes with the light of 200 million Suns in this NASA Hubble Space Telescope image.

Image Credit: NASA/ESA/CXC/SSC/STScI

Spiral Galaxy M101

Spiral Galaxy M101 viewed from three different NASA telescopes and kinds of light: Spitzer (infrared), Hubble (visible light), and Chandra (X-ray).

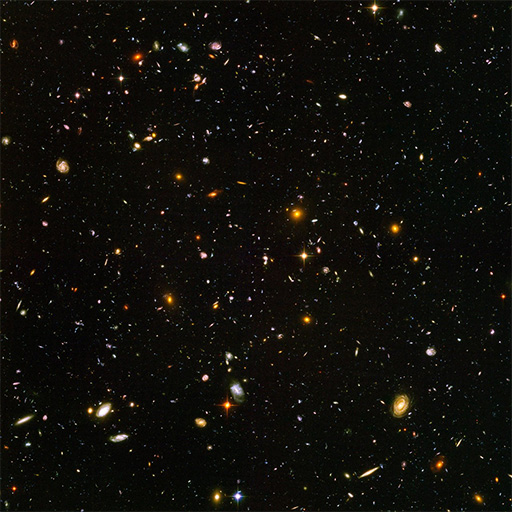

Galaxies

A galaxy is a huge collection of gas, dust, and billions of stars and their solar systems, held together by gravity. Some are spiral-shaped like our Milky Way Galaxy; others are smooth and oval shaped. NASA telescopes are helping us learn about how galaxies formed and evolved over time.

Image Credit: NASA/ESA/S. Beckwith (STScI)/HUDF Team

Thousands of Galaxies

Hubble Space Telescope picture showing thousands of galaxies. Even the tiny dots are entire galaxies.

Image Credit: NASA/ESA/M. Mutchler (STScI)

NGC 4302 and NGC 4298

Spiral galaxy pair NGC 4302 and NGC 4298. Astronomers used the Hubble to take a portrait of a stunning pair of spiral galaxies. This starry pair offers a glimpse of what our Milky Way galaxy would look like to an outside observer.

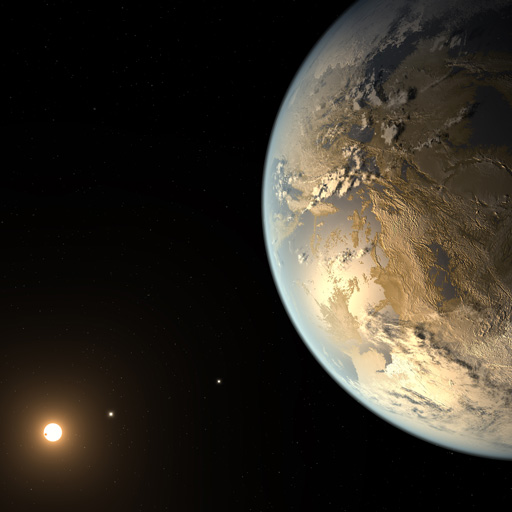

Exoplanets

Just 30 years ago, scientists didn’t know if there were planets orbiting other stars besides our own Sun. Now, scientists believe every star likely has at least one exoplanet. They come in a wide variety of sizes, from gas giants larger than Jupiter to small, rocky planets about as big as Earth or Mars. They can be hot enough to boil metal or locked in deep freeze. They can orbit their stars so tightly that a “year” lasts only a few days; they can even orbit two stars at once. Some exoplanets don’t orbit around a star, but wander through the galaxy in permanent darkness. NASA’s Kepler spacecraft and newly-launched Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite are helping us find more distant worlds

Image Credit: NASA Ames/SETI Institute/JPL-Caltech

Kepler-186f

Kepler-186f, the first rocky exoplanet to be found within the habitable zone—the region around the host star where the temperature is right for liquid water. This planet is also very close in size to Earth. Even though we may not find out what's going on at the surface of this planet anytime soon, it's a strong reminder of why new technologies are being developed that will enable scientists to get a closer look at distant worlds.

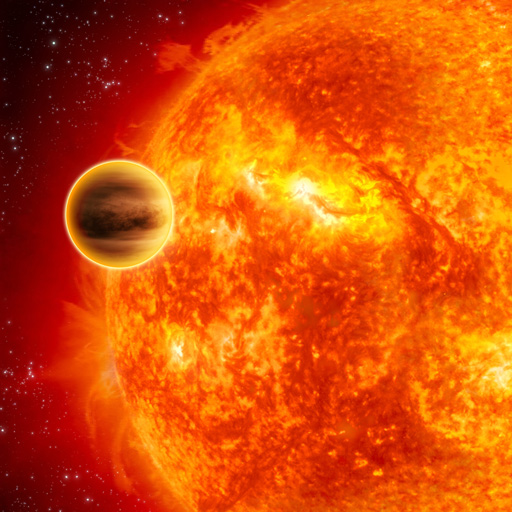

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

1 Pegasi b

1 Pegasi b. This giant planet, which is about half the mass of Jupiter and orbits its star every four days, was the first confirmed exoplanet around a sun-like star, a discovery that launched a whole new field of exploration.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech (artist concept)

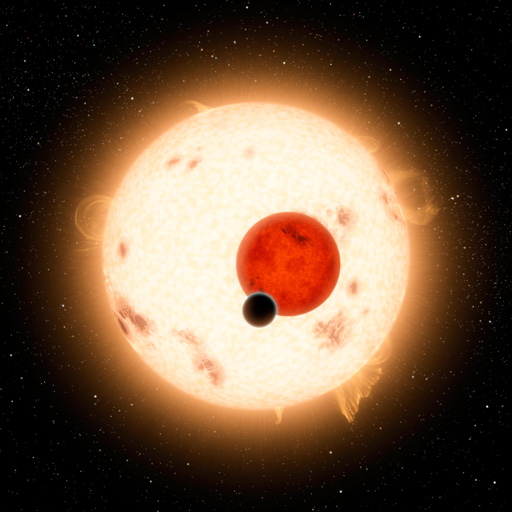

Kepler-16b

Kepler-16b. This planet was Kepler's first discovery of a planet that orbits two stars—what is known as a circumbinary planet.

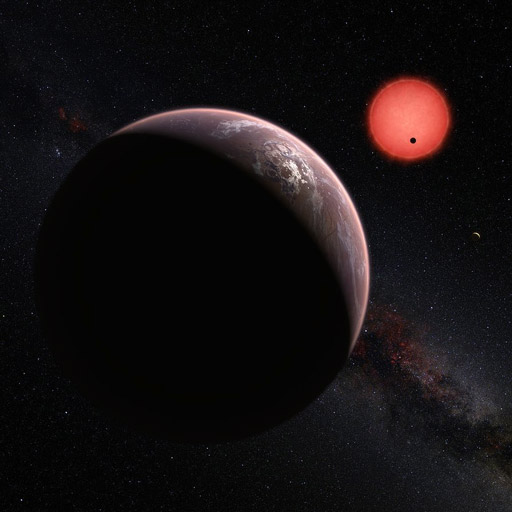

Artist's concept of TRAPPIST-1.

Image Credit: NASA

TRAPPIST-1

Using Spitzer, scientists found the most number of Earth-sized planets found in the habitable zone of a single star, called TRAPPIST-1. This system of seven rocky worlds–all of them with the potential for water on their surface–is an exciting discovery in the search for life on other worlds. There is the possibility that future study of this unique planetary system could reveal conditions suitable for life.